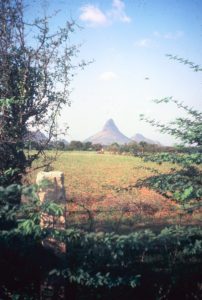

![]() Andrew and his young family arrive in South India in 1956 just nine years after India’s independence. His mission: develop ways to improve the lives of the people in the poorest area of Madurai District in Tamil Nadu, South India. The memoir details the excitement of adjusting to a new culture, learning the South Indian language Tamil, and application of the skills he had to help poor villagers, all of whom were Dalits, the outcastes of South Indian society.

Andrew and his young family arrive in South India in 1956 just nine years after India’s independence. His mission: develop ways to improve the lives of the people in the poorest area of Madurai District in Tamil Nadu, South India. The memoir details the excitement of adjusting to a new culture, learning the South Indian language Tamil, and application of the skills he had to help poor villagers, all of whom were Dalits, the outcastes of South Indian society.

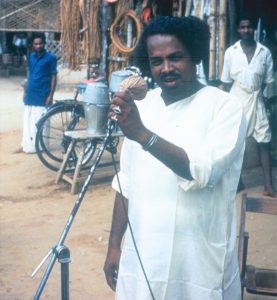

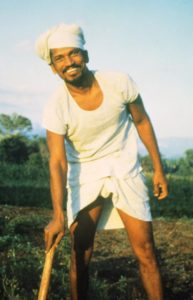

Home in India isn’t an autobiography. It’s a memoir covering Andrew’s introduction to India and his meeting and working with Indians during his first term (1956-1961) as a lay agricultural/rural missionary to the Madurai-Ramnad Diocese of the Church of South India in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. He fell in love with India and Indians. The book describes his feelings being there, some things he learned, the work he did there, and most importantly the people low and high he met who fascinated him and inspired him. The last chapter of the main part of the book describes what a wrenching experience it was for his having to leave India when the end of the first term came.

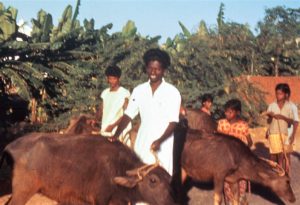

In the area where Andrew worked, many of the landless Dalits had converted from Hinduism to Christianity in the previous decade, before he and his family arrived in India. But his work was oriented to help all the Dalits in any village where he worked, Christian and Hindu.

The word Dalit refers to people in India who had previously been known as Outcastes, meaning they were so low on the societal scale that they were considered outside the caste system. Sociologists rightly tell us they were indeed a part of the caste system but had been assigned to the lowest place. The word ‘Dalit’ means ‘oppressed, crushed, broken, or trampled over’, which expresses how these people have been treated by their countrymen over the ages. During the time when Andrew was in India, the term ‘Harijan’ was usually used to refer to the Dalit people. Gandhi insisted on using that name to refer to the Dalits, ‘Harijan’ literally meaning ‘people of God’. But starting in the 1970s, there was a growing new identity among the Dalits that indicted the wider caste Hindu society for the stigma and suffering Dalits have endured through the ages.

‘Our Village’ in the book refers to Kallimandaiyam, which is located in the far northwestern corner of the diocese. Andrew and his family didn’t move there until October 1958, two years after the beginning of their first term in India. But it was there that Andrew’s real work began. Before then, the family was either in Bangalore learning Tamil at language school, or in Vatalagundu, (in another part of the Madurai-Ramnad Diocese) where he and his wife continued their study of Tamil.

Three people Andrew met and worked with in India were particularly important to him and to his understanding of village India and its needs—Raja Rao his Tamil teacher and two missionary colleagues: Rev. Ralph Richard Keithahn and Bishop Lesslie Newbigin. He’s written extensively about them in the book. Their stories including their interaction with him appear in the Epilogue.

In the end, his devotion to his work with the villagers comes into a major conflict with his dedication to his family and his marriage. Much of the memoir is devoted to telling the stories of his friends and colleagues in India who inspired him. It turns out that they are the primary reason why he was truly at home in India, loved India, and why he wrote the book.

As so many have said about their own experiences overseas, Andrew writes that he gained far more by being in India and interacting with Indians than whatever he may have accomplished in the village communities where he worked. India, he says, has given him immense rewards derived from the Indian people’s sharing their lives with him.

To purchase the book, click on this link.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For more information about Andrew Mills, please go to About the Authorr![]()

![]()

![]()